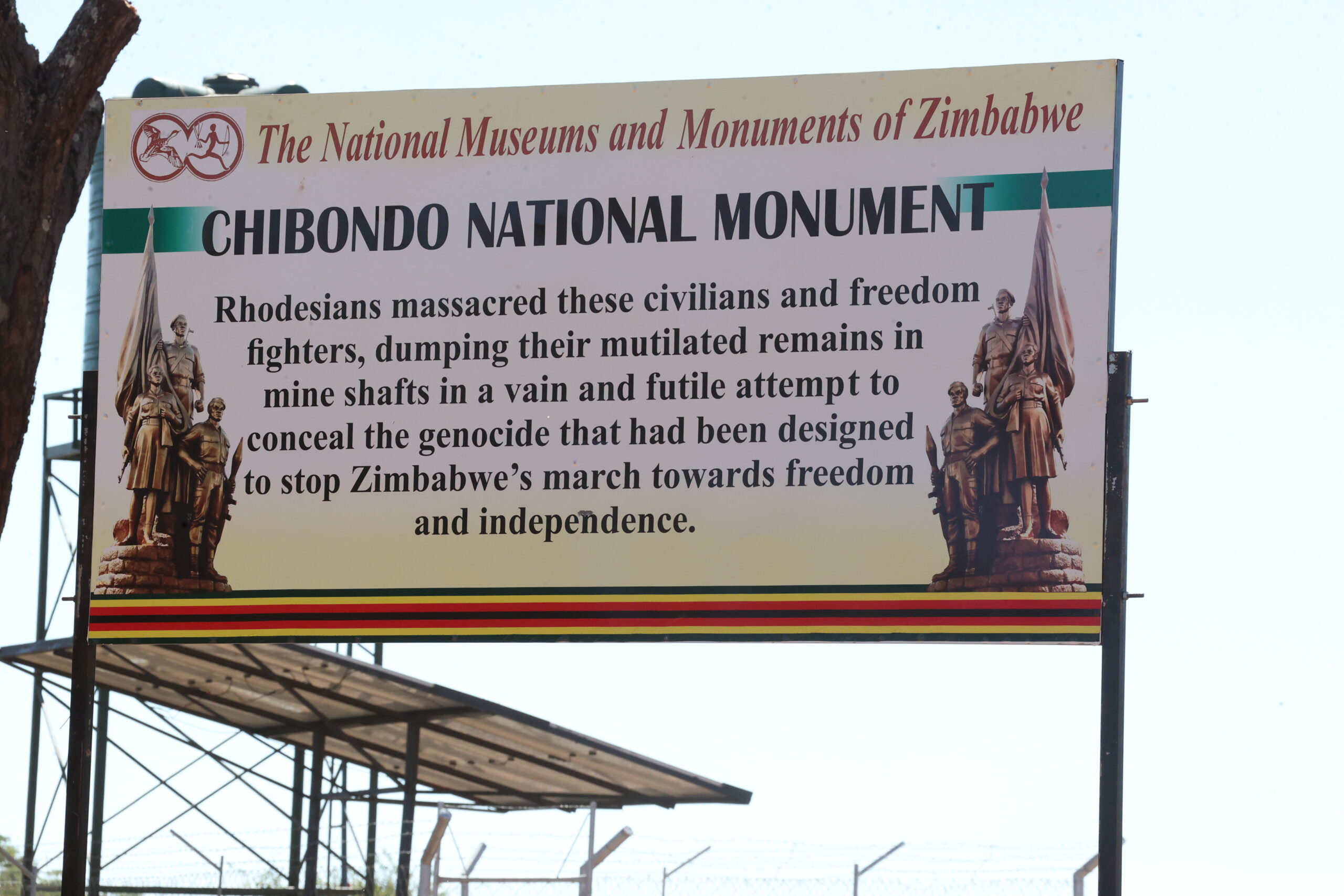

In April 2011, Zimbabweans were horrified at the gruesome discovery of bodies stashed by the Ian Smith regime in shafts at the disused Monkey William Mine, now better known as Chibondo. The bodies belonged to freedom fighters and villagers who were callously murdered from around 1972-1979 by the blood-thirsty Smith regime during the Second Chimurenga. Situated about 32 km from Mt Darwin Centre, Chibondo was at the heart of Matepatepa, the bastion of white commercial farming, and so it was the ideal place for the Rhodesian forces to conceal their genocide.

Soon after the discovery of the remains, the Fallen Heroes Trust of Zimbabwe, an organisation formed to identify mass graves and help in the reburial of the remains, moved in to exhume the bodies. In due course, the National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (NMMZ) declared the mineshafts a national memorial site.

As the exhumations gathered pace and the nation gripped by the sickening brutality of the Rhodesian forces, cheap politics came into play. For instance, some opposition politicians and activists refuted claims that the recovered remains were those of freedom fighters and villagers who were ruthlessly killed by the Rhodesian forces. As if that was not enough, a few days after the exhumations commenced, the High Court in Bulawayo ordered them to be stopped forthwith. In his ruling, Judge Nicholas Mathonsi cited objections to the ongoing exhumations by a shadowy group of war veterans. Cry, my beloved country!

The exhumations were subsequently terminated, much to the chagrin of the genuine war veterans and the despair of millions of patriotic Zimbabweans. Our Editor-in-Chief Munyaradzi Huni recently visited Chibondo Memorial Site and what he saw broke his heart. A tear fell. Read on . . .

When one walks into what is supposed to be the Chibondo Memorial Site, he/she is met by a sorry sight, one that that clearly confirms that something is horribly wrong. Torn and tattered canvas tents cover the entrances to about 4 deep mineshafts while the state of graveyard itself suggests that some volunteers had recently made spirited attempts to spruce up the site.

“We spruced up the graveyard, cleared the tall grass and erected those white crosses about 2 days before the national independence celebrations in Mt Darwin. Before that, this place was in a sorry state,” said Isaac Gochera, the local headman.

Before the exhumations came to a halt, the remains of 850 war casualties had been exhumed and reburied a few metres away. Some of the ex-freedom fighters who went down the shafts to exhume their colleagues’ bodies estimate that there could still be as many as 10,000 more bodies down there. At the height of the liberation war, Rhodesian forces were known to ferry injured and dead freedom fighters to the mine before dumping them into the shafts. They also rounded up villagers suspected to be sympathetic to the freedom fighters and herded them to the site, never to be seen again.

Once at the site, they executed the injured comrades and villagers, disposing of their bodies down the shafts to conceal their war crimes. There is no other way to describe such barbarity by the Rhodesian forces, except in one word — GENOCIDE. This was a well-calculated genocide that the Rhodesians thought they could hide from the rest of the country and, indeed, the world.

Chibondo is a dark reminder of the cruelty and the barbarism of the Smith regime. But, for reasons hard to fathom, the country is failing to preserve this site which is pregnant with our liberation war history. There is nothing at Chibondo to suggest that it is a shrine of such national importance. In one of his most famous quotes, American author, Robert Heinlein, warns: “A generation which ignores history has no past and no future.”

Another scribe famously wrote: “Monuments are for the living, not the dead. Preserve them, love them and pass it on to generations to understand their importance.”

Chibondo is our past, it is our present and it is our future. We can’t afford to neglect it.

In its current state, Chibondo is crying out for attention. We are not preserving it, we are not loving it and unless something is done about it, we will have nothing to bequeath to our future generations. Chibondo is a crucible of history and life-long memories, but we are not doing enough to give it the respect and honour it deserves. Chibondo cannot only be remembered during national events like Independence Day and Heroes’ Day. Chibondo is a constant reminder of where we came from and how dark that place was.

How did we get here?

To get to grips with the tear-jerking story behind Chibondo, the Brick by Brick magazine team visited the site and spoke to some of the local people. From their responses, it was obvious the sorry state of the shrine is something that is gnawing at their collective hearts.

Below, Headman Gochera gives his side of the story.

“I was born and bred in Dotito. In 1996, we were relocated from our homes in Dotito after the government announced plans to build a dam nearby. We were subsequently settled at Janhi Farm in Centenary, which was already home to a thriving cooperative. After just one agricultural season, things came to a head after the cooperative hierarchy told us in no uncertain terms that we had overstayed our welcome. Despite our protestations that it was government’s decision to resettle us at Janhi, there was no amicable solution.

“We were given a 7-day notice to vacate the farm. We appealed to the Mt Darwin district administrator (DA), who instructed us to go back after which he promised to address the cooperative bosses. We went back, but after the 7-day ultimatum was up, we were told by the cooperative leaders to pack our bags. We went back to the DA’s office, this time with all our possessions. I remember he called a roundtable meeting at his office to deliberate on the matter.

“When we left Dotito to pave way for the dam, there were about 14 families. However, by the time we returned to the DA’s office with our worldly possessions, only 6 families came along. The other 8 families remained behind in Centenary. To our relief, the DA’s office conceded that they had erred by resettling us at Janhi Farm.

“The DA’s office instructed us to go to Matepatepa while they worked on the modalities of our final settlement. According to the DA, our proposed new home was in a densely forested farm belonging to the government and required extensive clearing to make it habitable. We got into our scotchcarts and settled here at Chibondo under Matepatepa. This was in December of 1997. The other 8 families joined us shortly afterwards, so did 9 other families, bringing the total to 23.

“When we first settled here, this place was nothing but thick forest and we allocated ourselves pieces of land on the 1,400-hectare farm. We spent 4 days pegging our homesteads and plots, after which the DA regularised our stay here.

“To be honest with you, when we settled here, no one had the faintest idea there were shafts/tunnels underground. It was only after Christopher Gochera’s family cultivated the land that the first dead bodies were found.

“A few months after our arrival, there were rumours that some gold panners led by one Godfrey Kapingidza had discovered gold around this area. The amount of gold discovered kept on increasing, thereby attracting prospective miners from far afield. One of those attracted by the glitter of gold was a policeman by the name Makwende, who came along with his wife, who was into gold mining in Mt Darwin. In fact, most of the resettled families turned to gold panning as their livelihood. Incidentally, our biggest customer was Makwende’s wife, who had opened a general dealer’s shop right here in the village.

“After sometime, Makwende realised that Chibondo was abound with gold and decided to formalise his mining activities. He encouraged us to form a syndicate led by his wife. This we did. One day the Makwendes collected the syndicate’s gold and came back driving a brand-new car along with security guards to keep an eagle eye on mining activities in the area. To our surprise, the security guards told us that we were no longer allowed to mine gold without the Makwandes’ permission.

“One day, as some panners were digging for gold during the night, they fell into a very big shaft. When they landed at the bottom of the shaft, they were shocked to see dead bodies. Frightened out of their wits, they scrambled out of the shaft and word about their grisly discovery quickly spread. However, no action was taken at the time.

“On discovering that Makwende was now intent on pushing us out of the lucrative gold mining project, some young men lured another gold dealer called Zakazaka. Makwende and Zakazaka clashed repeatedly until Zakazaka was forced to seek relief from the Ministry of Mines. The two protagonists eventually dragged each other to court, with Zakazaka emerging victorious.

“Before resuming his mining operations, Zakazaka sought the help of the Fallen Heroes Trust to exhume the dead bodies from the shafts. Led by [Andrew] Chikukwa, members of the Fallen Heroes Trust called for a meeting which was attended by a wide spectrum of stakeholders including the police, DA’s office, Chief Kandeya and local spirit mediums. They were camped here for 2 days in 2011 while conducting traditional rituals.

“Chief Kandeya led the rituals to which I was also invited as the village headman. After the rituals, some members of the Fallen Heroes Trust went down the shafts and started exhuming the bodies. In all, about 850 bodies were exhumed up to the point the exercise was halted. According to the Fallen Heroes Trust, there were still many more bodies buried in these shafts compared to the numbers exhumed.

“When they stopped the exhumations for safety reasons, they left one of the bodies near the entrance to the shaft. The comrade’s spirit manifests itself among various people reportedly saying makandisiya pamukova weshaft. Ndiburitseiwo sezvamakaita vamwe (You left me near the shaft entrance. Please take me out like you did to my fellow comrades).

“This is my story as it pertains to the bodies found at Chibondo. Due to time constraints, I had to be very brief, but I hope I have given you an accurate picture on how we found ourselves here and how the shafts were discovered. I am shocked when I hear some people claiming the discovered bodies were those of victims of political violence between Zanu-PF and the opposition.

“When we settled here, the [Movement for Democratic Alliance] MDC did not even exist. We have been living here since 1997 and in that time we have never seen people coming here in suspicious vehicles that could have been used to ferry all these bodies. I think members of the Fallen Heroes Trust can take up the story from where I have left off.”

Exhuming the dead bodies and tears of grief

A former freedom fighter, David Tawona Chigumbu is the chief security officer of the Fallen Heroes Trust of Zimbabwe. Naturally, Chibondo stirs heart-rending memories for him.

Says Chigumbu: “We came to this site after stories that dead bodies had been discovered in the shafts here. After the mandatory rituals, I was part of Fallen Heroes Trust team that went down the shafts to exhume the bodies with the help of geologists. We also worked in collaboration with officials from National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe.

“What we saw shocked us. It will stay with me until my dying day. We found some remains stashed in drums that apparently contained acid. Some of the bodies had been reduced to powder. We saw several bodies riddled with bullets. We came across women who were buried with children strapped on their backs. There is shocking horror in these shafts.

“We did our best to ensure that the bodies were not mixed up. Altogether, we exhumed 850 bodies, which we reburied nearby. I cannot give you the correct figure of the unexhumed bodies, but I can tell you that there are many more bodies still buried in the shafts. There are about 3 big shafts that are very, very deep.

“There are also some small shafts scattered around this area. It’s actually risky to walk around this place since there are several shafts which have not yet been identified.

Chigumbu corroborated Headman Gochera’s recollection of the body of a freedom fighter left at the mineshaft entrance: “It’s true, we left the body about 5 metres from the entrance of the shaft. When this dead man’s spirit speaks, it identifies itself as Cde Chipembere, a detachment commander during the liberation war. I actually worked with him during the war. I worked with quite a number of freedom fighters whose bodies were discovered here,” says Chigumbu.

According to the NMMZ, the main shaft is approximately 90 metres deep. The exhumations could not go beyond the 90 metres for safety reasons. The first stratum of the shaft was 0-50 metres deep, and consisted of highly decomposed bodies mostly in skeletal state which were also highly defragmented and could not be assigned individual status. It is believed that the bodies were bombed to destroy the evidence.

Speaking to the media in 2018 during an exhibition of the Chibondo Genocide, the curator and historian at the National Heroes Acre, Rumbidzai Bvira, said:

“Two important dates emerged from this stratum: 1976 (Southern Rhodesian Identity card of Phanuel Kahowa) issued at Mt Darwin on the 8th of May 1976. The original Mt Darwin stamp is still visible and readable. This evidence corroborated the oral testimony of his son who said his father was abducted on 11th July 1976 at 5.00pm and was never seen again until April 2011 when the exhumations at Chibondo happened.”

She revealed that the middle strata (50-70 metres deep) recorded a high prevalence of uniformed combatants with high occurrence of Chinese uniforms as well as Russian, Yugoslav and Ethiopian uniforms. A lot of military paraphernalia was recovered here. The bodies were mostly intact as they were exhumed from a mixture of water and acid which helped to preserve them. The stratum was dated 1974 on the strength of a copy of the Rhodesia Herald which was recovered from the pocket of a combatant’s military fatigues.

According to Bvira, the lower stratum (90 metres and below) and much below the wet line had bodies that were intact. Decomposition only occurred when the bodies were brought to the surface. Although the exhumations were terminated at 90 metres this was, however, not the sterile level of the stratigraphy as bodies continued to be found below this surface and in other shafts.

The chairman of the War Veterans office in Mt Darwin, Andrew Chikukwa, has his fair share of memories on Chibondo, which he shares below with Brick by Brick readers.

“In 2010, when I was the secretary in the War Veterans office, we received reports that dead bodies had been discovered at Chibondo. According to the reports, the bodies were discovered by [artisanal] gold miners who had fallen into a disused mineshaft. In response to the reports, we teamed up with members of the Fallen Heroes Trust to begin work on the exhumations.

“When the [artisanal] miners made the discovery, they stopped mining and immediately made efforts to have the bodies exhumed. We subsequently alerted the government, through the Ministry of Home Affairs, of the discovery. The whole country was soon informed. Chiefs from around Mashonaland Central, spirit mediums from Mt Darwin and all over the country descended on Chibondo and literally camped here.

“Before exhuming the bodies, traditional rituals were conducted to appease the spirits of the deceased comrades. The spirit mediums conducted a series of rituals, which resulted in torrential rains falling here. I remember one of the spirit mediums consulted was Tateguru Nyangonhete. The rituals were followed by a gun salute. Cde Kachidza, who was the chairman of the war veterans’ association in Mt Darwin at the time, was given a gun and he fired bullets into the air while standing next to the biggest shaft. The firing of the gun signalled that the spirit mediums had agreed to the exhumation of the bodies.

“When the exhumations started, we worked in shifts. There were so many bodies in the shafts and this was not an easy operation. About 850 bodies were exhumed over several days. Going down the shafts, we discovered that some of the bodies were piled on top of each other. What really broke our hearts was the fact that among the bodies were those of women and children. I thought I should mention this because we discovered the body of a woman with a baby still strapped to her back. We also came across grenades inside the shafts. The grenades were still intact and so we had to tread very carefully down there. We also discovered large amounts of acid inside the shafts. The stench was nauseating.

“From the Fallen Heroes Trust side, those at the forefront of the exhumations included the late Cde George Rutanhire and Cde Gumbeze, who was the chief field officer.

“As the comrades exhumed the bodies, it soon became apparent that the exercise was now becoming too dangerous. There were genuine fears that the exhumers were in real danger of being trapped underground and suffocating to their deaths if the shaft walls collapsed. The situation was just too precarious. These shafts are not supported by anything and so there were fears that they could collapse anytime due to the pressure of human traffic. A very tough and painful decision was then taken to terminate the exhumations.

“And, yes, it’s true, when the exhumations stopped, Cde Chipembere’s body was the next in line to be taken out of the shaft. But this was not to be as it was abandoned very close to the entrance.

“I also recall that the bodies of 3 spirit mediums were exhumed from one of the shafts. The body of one of the spirit mediums was taken by his relatives while the other was buried under strict traditional protocol at a secluded place nearby. In line with tradition, we are not in a position to show you the burial site. It’s taboo in our culture to do so.

“The bodies we found in these shafts are clear testimony of the sheer brutality of the Smith regime. It was not just the bodies of former fighters that we discovered, but those of women, children, girls and boys. That was how ruthless the Smith regime was. Why were they killing innocent women, children, boys and girls? The dead bodies are also proof that people of all ages played a role in the liberation war. Zimbabweans from all spheres and age groups came together to contribute to the war effort in one way or the other.

“We also discovered, to our horror, that the bodies dumped in the Chibondo mineshafts belonged to people from different parts of Zimbabwe. After killing people all over the country, the Smith regime carried the bodies and dumped them here. The Smith regime knew about these German shafts and they were mistaken to believe that we would never discover these bodies. These shafts are very deep and once underground, they scatter in different directions.”

‘Going down the shafts killed me several times’

And then came the pleas to “please preserve Chibondo and save the future”.

Never one to pass the buck, Chikukwa got the ball rolling.

“When the exhumations were stopped, our hope was that the government would fence off this area. If these shafts are left open as they are, there is a danger that the village folk and/or their livestock will fall into them. As it is, we just covered the entrance to the shafts with tents but, as you can see, when it rains, water flows into the shafts.

“Like I have said before, this area is rich in gold. Some gold panners still come during the night in search of the precious metal. We must make sure that the panners don’t come here anymore.

“We need to preserve this site because it speaks a lot about the history of this country. This is one of the places that proves, without doubt, the cruelty of the Smith regime. We should also put a stop to this practice where this place is only spruced up during national events like Independence Day or Heroes Day. This place should be preserved as a national heritage site. We should respect the people whose bodies were dumped in these shafts,” said Chikukwa.

Former freedom fighter Chigumbu could not hold back his tears as he relived the bitter memories of the Second Chimurenga.

Reflecting on his liberation war days, Chigumbu says: “As a former freedom fighter, it pained me to see my fellow comrades in these shafts. It pained me to see women and children in these shafts. We won the war because the povo [civilian population] rallied behind us. Without these mothers, without these children, without these boys and girls we would not have won the war. Our mothers cooked for us. They carried their babies on their backs as a decoy as they brought us food to our bases. The boys and girls were our mujibhas and chimbwidos. They were our means of communication. My heart bleeds when I recall what I saw down these shafts.

“I came across the bodies of some comrades that I fought side by side with during the war. I saw Cde Garry Brighton here. I saw Cde Chipembere here. I saw Cde Soft Guy here. I saw Cde Chovhai Mabhunu here. These are some of the comrades I fought alongside with from around 1972. I trained with some of them at Mgagao in Tanzania. Going down the shafts and seeing my comrades was torture. I died inside several times as I went down these shafts. As I stand here, I am dead inside. I don’t know how to express what is going on inside me. Sometimes, I feel like it’s a dream, but then I saw my fellow comrades. It hurts. It kills you. Sorry, Cde Huni, I can’t stand this. This is killing me daily.”

Obviously overcome with emotion, Chigumbu paused as he broke down in tears.

When he had regained his composure, Chigumbu continued: “For years we were wondering where these comrades had been taken to after succumbing in the heat of battle. Now we know, the cruel Smith regime killed them and dumped their bodies here. I am in pain. The pain kills me everyday. I am happy that [the spirits of] these dead comrades directed us to where their bodies were dumped. I know they were not resting in peace inside these shafts.

“They were piled on top of each while some were thrown into acid. They were reduced to powder. I saw the powder in drums. I said Mbuya Nehanda chiiko ichi? I said Sekuru Chaminuka chiiko ichi? Ndivo mapfupa amaitaura here aya? Mwari vari kumatenga chiiko ichi? (Mbuya Nehanda, what does this mean? Sekuru Chaminuka, what is the meaning of all this? Are these the bones you spoke about rising again? God Almighty, what is going on?)

For the umpteenth time, Chigumbu broke down.

In between sobs, he continued: “After discovering these bodies, my wish and my appeal is that we look after these comrades well. Zviri nani ini hangu mupenyu ndishaye chandinacho asi tachengetedza vamwe vedu ava (I feel priority should be given to honouring these dead comrades. I don’t mind living in abject poverty as long as these fallen heroes are well taken care of). Everyone down those shafts fought in the liberation war. Let’s make sure their death was not in vain by preserving this place [for posterity]. Let’s preserve Chibondo so that our children can appreciate that we value the legacy of those who died for this country.

“The young generations should come here for inspiration. They should come here to see how cruel the Smith regime was and to study their true history. But the younger generations will not come here if we neglect this place. They will not respect us if we don’t respect ourselves. And they will not respect our history if we don’t respect it ourselves.

“When I look at myself, I say, I am much better off. I don’t have much, but at least I survived to witness a free Zimbabwe. How about these comrades who were butchered by the Smith regime and dumped here? Wherever they are, their spirits will not rest because we are in a free Zimbabwe but we are not giving them a deserved rest.

“Why can’t we set up a library here where the history of this place and the true history of Zimbabwe is told? This is not the only place that we are failing to look after. There are many other such places within and outside Zimbabwe. Ngatiitei kuti nzvimbo dzese idzi dziyevedzewo (Let’s make all these places more appealing) so that the young generation will be attracted to come and learn our history.”

Chigumbu also made another interesting revelation – that among the exhumed bodies were those of Frelimo [Front for the Liberation of Mozambique] cadres.

“In one of the bays at the graveyard, we buried comrades we exhumed who were putting on Frelimo uniforms. As you know, during the war, some Frelimo comrades helped us and some of them died during attacks by Rhodesian forces. We would come from the rear into the battlefield with some of our comrades from Frelimo.

“They had already freed their country [in 1975] and so they sometimes would fight alongside us while wearing their Frelimo camouflage. While most of them did not go deep into the battle zones, quite a number joined us on the battlefield. Sometimes we were attacked soon after crossing into Rhodesia and some of our comrades, including our Frelimo brothers, were killed.

“After a battle, the Rhodesian forces would take with them all the dead and wounded. We used to wonder where they were taking all these bodies to, but we now have the answer. They shoved the wounded and dead comrades down these mineshafts. That is how cruel they were. We exhumed the bodies of 42 Frelimo comrades, which we buried in a separate bay.

“As Zimbabweans we should know that white people don’t like to see us living in peace because they know how rich our country is. They will do everything in their power to divide us. Vanoita inonzi makono tunganai mumba menyu. Imi muchitungana ivo vachiba hupfumi hwenyu. (The white man will cause you to fight while they are busy looting your God-given resources). After creating divisions among us, they will come and pretend as if they want to help us unite by talking about things such as democracy, human rights, etc. How can they unite us when they are the very same people who divided us in the first place?’’

Chigumbu, whose Chimurenga name was Cde Tendai Mugomomuneshumba, quit school to join the liberation struggle in 1972 after which he received military training at Mgagao, Tanzania.

Born in 1958, Chigumbu joined the liberation struggle when he was just 14. “I trained with people like Cde Edwin Munyaradzi, Cde Mbereko, the late Cde Vitalis Zvinavashe [former Zimbabwe Defence Forces commander], Cde Edson Ziso, Cde Bombadiari and Cde Soul Sadza at Old Mgagao,” he told Brick by Brick. On completing his training, he was deployed on the warfront in 1974 where he operated under the Chaminuka Sector in Mozambique’s Tete Province.

Pedzisai Chabaya was among the first families to relocate to Chibondo in 1997 under Headman Gochera.

He recalls: “I was among the first families to be resettled here. To us, it was our new home. Little did we know that one day the bodies of freedom fighters would be retrieved from the nearby abandoned mineshafts. However, we were relieved that the bodies of our ‘missing’ brothers and sisters had been found and that they would, at long last, be given a decent burial.

“Generally, this area does not receive much rain. However, when the bodies of 3 spirit mediums were exhumed on Day 4 the skies opened up. Dark clouds gathered and in no time it rained heavily around Chibondo.

“However, we are now facing challenges because the comrades whose bodies are in the shafts are demanding to be exhumed as well. Their spirits speak through different mediums in surrounding villages. If you take a walk around this place, you hear the mysterious voices crying, but when you turn around there is no person in sight. Some of the spirits can simply possess a child and start saying: Zvamakatisiya, mati toita sei? Tichasvika riinhi tichingori munzvimbo ino? (You left us down in the shafts, what do you expect us to do? For how long are we going to be stuck in this place?)

“Some of us who went down the shafts/tunnels can understand why the comrades want to be exhumed. The majority of the bodies down those shafts were piled haphazardly. Some were standing with their hands raised up, others in a sitting position while still others were dumped on top of others. In short, all of the bodies were piled in extremely uncomfortable positions.

“What pains me most is the fact that the exhumations were called off just as we were about to take out our fellow comrade, Cde Chipembere Mhukayesango. There were fears that the tunnel was going to collapse and so we left him just a few metres from the entrance to the main shaft. His spirit manifests itself in different people around this area pleading to be taken out of the shaft. We are appealing to the government to make a concerted effort to bring his remains out of the shaft. It appears as if his spirit is really tormented and it bothers us.

“We buried the remains of the exhumed comrades in those graves you see over there [pointing in the direction of the grave site]. However, I am appealing to the government to build decent graves for these departed comrades and brighten up this place. We need to look after this place well so that our children can come here and see for themselves how cruel the Smith regime was. If you go to Chimoio in Mozambique, those mass graves are well looked after and if one gets there, he/she can see that the government cares about the comrades who were ruthlessly killed by the Smith regime. Let’s do the same here at Chibondo and all the other places with such mass graves. These comrades deserve to rest in eternal peace.”

Chibondo falls under Magamba District, whose chairman, Kiswell Kadere, has an interesting tale to tell.

“Magamba District got its name long before the discovery of the dead bodies in the shafts. When we first settled here, we did so under the jurisdiction of Munhumutapa District. However, due to overcrowding we decided to seek greener pastures, but we had no idea what we would call our new home. After some heated discussions we agreed to call it Magamba District.

“As you are aware, ‘gamba’ means ‘comrade’ in our Shona language. We named this district Magamba way before the discovery of the remains of dead comrades in these mineshafts. To me, it’s not mere coincidence. The spirits of these comrades were already communicating with us. It’s true when they say that mweya wevafi unopinda kuvanhu vapenyu (the spirits of the dead speak through the living).

“When the bodies were found, we were grief-stricken, but happy at the same time that our fellow comrades would at long last be given decent burials. A school – Magamba Primary School — has since been built in honour of the fallen comrades. Unfortunately, lack of resources has stalled its completion.

“When we reburied the comrades in that graveyard, I was hopeful that the government would contribute towards the erection of tombstones. If we remove those white crosses depicting the graves, it’s hard for anyone to know that this is, indeed, a graveyard. It is our duty as a nation to look after this place well. Let’s show some respect to the comrades who gave up their lives to liberate this country from colonialism.

“To make matters worse, the shafts are still open and there are still thousands of unexhumed bodies down there. We need to put up a shed or other structure to protect the shafts so that when it rains, water does not flow into them. When it rains, the stench that comes out of the shafts is unbearable. You can’t even get close to them. Only the entrance is covered by tents. As you can see, some of the tents are now weather-beaten,” Kadere said.

Headman Gochera echoed Kadere’s sentiments: “I, too, am sending an SOS to the government. These shafts are still open and it worries me everyday. In our tradition, under Chief Kandeya, guva rikarara risina kuvigwa munhu, as the headman of the area, the chief has every right to ask me to pay a fine. Zvinoyera kuchera guva rorara risina kufutsirwa. In Shona, we say aya ndiwo anonzi makunakuna. Nzvimbo ino haife yakanaya mvura zvakakwana nenyaya iyoyi (It’s taboo to leave a grave open once it has been dug. Until we right our wrongs, we will suffer from perennial droughts . . .)

“When the exhumations were stopped, these shafts were left open yet there are dead bodies inside them. These shafts are like guva risina kufutsirwa. We just covered the entrances to the shafts with tents. In our Shona tradition, we say nzvimbo ino yakasviba (this place is now under a spell). We need to conduct some more rituals to cleanse this place because the comrades who are still in the shafts are angry with us.

“While we await a long-term solution to preserve this place, why can’t we put up a shed to cover these shafts? We have to protect the dead bodies from the rains. We must show them love and respect. This is causing me sleepless nights. The National Museums and Monuments says the mineshafts are now their responsibility. But, if that is the case, they should demonstrate it through their actions that they have, indeed, taken over and not leave this important place in this deplorable state.

“It does not make sense to run around and spruce up this place in time for national events like Independence and Heroes’ days. We have an old man working here, but he cannot do much because he doesn’t have the necessary tools. Sometimes he goes for months without pay, but he remains committed to his work.

“If the government has plans to exhume the remaining bodies, we have the land to rebury the comrades. We have about 10 hectares reserved for that purpose. All we are waiting for is feedback from the government.”

Bruce Chikotora, a representative of Chief Kandeya, also shared his views: “I want to confirm that what is happening in Chibondo is makunakuna in our tradition. Nzvimbo ino yakasviba (a spell has been cast on us) and because of that zvinhu hazvifambi zvakanaka (we are going to experience a litany of challenges). It’s now over 10 years [since the exhumations were called off], yet these shafts remain open. This is against our culture. I urge the government to attend to this issue [as a matter of urgency].

“Chibondo is blessed with so many resources, besides gold, but as long as the spirits of the dead comrades are not appeased we will not benefit from these resources. The comrades whose bodies were dumped in these shafts died fighting to free Zimbabwe. They are disappointed that they have not been given a decent burial.

“Let’s preserve this place so that Zimbabwean children countrywide can come here and learn about its history. Chibondo is a good example of how hard it was to attain our independence and it is my wish to see this place preserved so that current and future generations will never forget where we came from. This place can also act as a magnet for foreign tourists. We have a rich history. So let’s make sure we preserve it.

“I would like to thank President Mnangagwa for giving about 800 soldiers the opportunity to come here to learn first-hand about the history of the liberation war. This is a good start. It is our fervent hope that many more people from all walks of life will come here to learn about this kind of history.”