* It’s definite: Zimbabwe has oil and gas in the Muzarabani-Mbire Basin

* Other countries drilled over 200 exploration wells to declare a commercial discovery

* Zimbabwe did it with just one well

* Nation could have 50% of the proceeds from oil and gas, instead of the 5% other African countries are getting

* Production-sharing agreement puts Zimbabwe in pole position

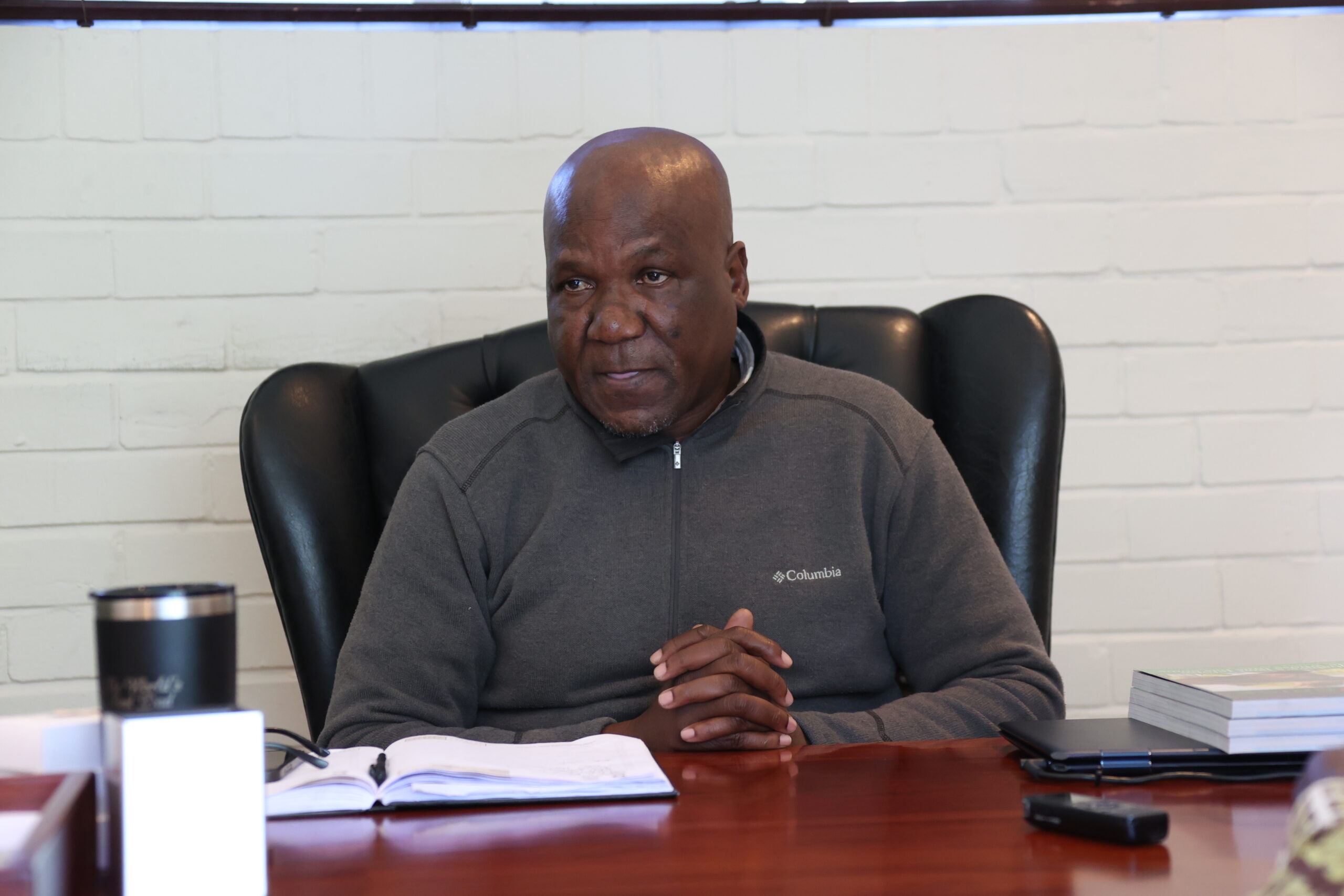

In Harare’s leafy suburb of Borrowdale sits Paul Chimbodza, the Managing Director of Geo Associates, a man whose patriotism goes before him. From well-appointed offices in Borrowdale, Geo Associates acts as the lead local entity in the Muzarabani-Mbire Oil and Gas Project. From a Zimbabwean point of view, Chimbodza is good news on two legs.

Brick by Brick interviewed him on 27 April 2023, and his words were sweeter than the proverbial honey: “… Do we have oil and gas or not? That was the reason we drilled Mukuyu-1. And we answered that pertinent question. And the answer was yes! We do have hydrocarbons in the Muzarabani Basin … We are very excited because I can share with you that in other jurisdictions, like East Africa, they had to drill more than 200 wells before they could declare a commercial discovery. For us to hit hydrocarbons in our first well is a huge, huge, huge, huge plus, and we are very proud of that.”

And Chimbodza was not finished: “For Zimbabwe, the country took a deliberate decision to say we want to see local participation of our sons and daughters in the mainstream economy, and that is why I never left Zimbabwe to go and seek work abroad. I can work anywhere in the world, but I believe in the geology of my country, and I also believe in the leadership of my country.”

No wonder he wears two hats – one as a promoter and shareholder of the oil and gas project, and the other as a patriot born and bred in Zimbabwe. Our editors Munyaradzi Huni and Baffour Ankomah interviewed him.

Q: Let’s start by you giving us an overview of the project, the whole background.

A: Ok. I am the managing director of Geo Associates, a Zimbabwean registered company, which was registered way back in 1996. It started work as a consulting entity in the space of geology and mining. I am a geologist by qualification.

Some years back after being made redundant by my employers, instead of going home and cry about it, we morphed ourselves into a consulting concern. So we did a lot of consulting work both locally and regionally, but at that time we did not realise that in the consulting space you are playing on the fringes of the mining industry.

So we decided to change our business model to one that talks to the acquisition of mining title and use our own inhouse expertise where we take the project as far as we can. It means just from a mere licence, we validate our project and at a certain level, we bring in the big brothers with deep pockets.

Understandably this business is quite an expensive undertaking. So out of that model of progressive projects, from acquiring the assets and taking it up the value chain in terms of doing explorations, we can fast-forward to today where we have two key projects that we are very proud of as Zimbabweans, because we incubated these projects from scratch.

The first one is the Arcadia Lithium Project which we incubated up till last year when we offloaded it to a Chinese entity. That went through the model that I am describing to you where we had the project 100% in our grasp, and then we took it down the curve exploration-wise, and then brought in partners. Fortunately, the results were positive, and today we see a world-class lithium deposit and producer in the mold of Arcadia.

The second project is the Muzarabani Oil and Gas. Again, it is a project that we incubated internally as Zimbabweans, then brought in an Australian entity by the name of Invictus to join us in the exploration.

Exploration by its nature is a high-risk and high-intensive game. You are spending money without any guarantee of a discovery and that tests people. So kudos to our partners Invictus who saw the potential in the project and us who are involved, and most importantly saw the potential in Zimbabwe.

They came on board and we have, over the last 4 years, now advanced the Muzarabani Oil and Gas Project into quite a significant oil and gas project, in not only in Africa but globally.

You may be aware that we have drilled our first well, the Mukuyu Well. We finished drilling Mukuyu just around the end of December last year. It was drilled down to a depth of about 4,000 metres, that is 4 km.

The reason why you found the rig taken down when you visited are twofold: The first is that we finished the drilling just before the onset of the rainy season and that rig when it is mounted, the mast goes up to 50 metres high. So it is probably the tallest structure within 50 km, and that obviously puts it at risk of lightning strikes, and Muzarabani is notorious for lightning strikes.

The second reason is that when we drilled to 4,000 metres, we had actually stretched the rig to beyond its capacity, which was a good thing for us because we continued to see exciting things.

So we took the opportunity to use the rainy season when our staff went for a short break to service the rig in preparation for the drilling of a second well, which is Mukuyu-2 that is coming up this year. Our staff have started trooping back to camp and we will be drilling Mukuy-2 sometime in early July 2023.

This is obviously a very technical space. You may recall that last year we issued an update to the market. Our partners Invictus are listed, so they are obliged to share with the market any news whether positive or negative. So last year we shared some information based on the results of Mukuyu-1. Unfortunately, that update was not interpreted well by the man in the street. But let me repeat to you here what we found.

We drilled Mukuyu-1 down to 4,000 metres. This was the first ever oil and gas exploration well to be drilled in the Zambezi Basin. The reason for drilling that well was to ascertain whether we’ve got oil and gas. Very simple – do we have oil and gas or not? That was the reason we drilled Mukuyu-1. And we answered that pertinent question. And the answer was yes! We do have hydrocarbons in the Muzarabani Basin.

Normally, after drilling your exploration well, you want to do what we call appraisal. Yes, the well answered the pertinent question: do we have oil and gas or not? If it is a yes, as in our case, you want to appraise the well, and appraisal is talking beyond discovery. It is talking more on the questions: are the hydrocarbons able to move in terms of porosity? How much is the flow rate, and other technical things? So you then start to appraise.

So our team, because of the excitement of the positive results we got, decided to appraise Mukuyu-1. This is where we ran into technical problems to do with our equipment. We sent down one of our sophisticated equipment into the well to measure the concentration of the oil and gas, and also to extract a sample from our 4,000-metre depth.

Unfortunately, that piece of equipment failed when it was sitting at 4,000 metres underground. This piece of equipment cost about US$4.5m. On a rig platform, you have so many service providers. There is the guy who comes with the rig, and in our case there are 6 other guys who are giving supportive services. So if one of them becomes a weak link, then we run into problems. Unfortunately, we had one of our service providers becoming a weak link, and that is a good learning curve for us.

Now the way it works is that if a service provider becomes a weak link, and another service provider among the 6 has got his piece of equipment standing idle for 10 or 20 days as a consequence of the weak link, they will be charging standing time for all those 10 or 20 days. And we are talking sums in the order of US$100,000 a day. So we had to, by all means, try to make sure that the piece of equipment sitting at 4,000-metres underground work. Unfortunately, it did not work, and we decided to pull it out.

When we then made the announcement to the public, our announcement concentrated more on our failure to appraise the successful exploration well. The announcement didn’t concentrate on the success of the well in finding hydrocarbons in the Cabora Bassa Basin.

So depending on where one is sitting, people would take the negatives of our failure to appraise as the main issue, and not our failure to get hydrocarbons, which is what happened. Our failure to appraise, because of the failure of one equipment and our decision to pull it out, became the issue.

The market reacted by saying: “huh, they are pulling out of the Zambezi Valley”. No, that was not the case. But we take the blame for not crafting our statement properly. Unfortunately, the statements are made by our partners Invictus who are sitting out of Perth in Australia. So they have certain templates they use to address their shareholders.

We had to do another update locally for our local stakeholders in a more simplified manner. Because we understand this very high technical field, sometimes it is very difficult to simplify some of the technical language, so the meaning gets lost in technical jargon.

But, that as it may, I can safely say that inhouse we are very excited because we have a very successful well in Mbire. What that has proved is that the Muzarabani Basin, as a geological address, contains hydrocarbons, and hydrocarbons is the term we use for both oil and gas.

Mukuyu-1 cost us in the range of US$18m to drill. We are galvanised by the results of that well to go and do a second well. So logic demands that no one in their right senses would go out there and spend that sort of money on a second well if there is nothing there to find. So we are very upbeat about the positives. We learnt a lot of technical lessons from Mukuyu-1. We are now going to do Mukuyu-2, and we are also starting preparatory work for probably a third well.

The industry we work in, in fact by global standards, we have done extremely well in terms of the timeframe between being licensed and drilling the first well. In other jurisdictions, it would take 10 years to do what we have done in 4 years. And we want to do it quicker. For us to do 2 wells within a period of 4 to 5 years is extraordinary by global standards.

Our team, like I said, has started trooping back to the ground in preparation of the drilling of Well No.2, which would be influenced by the technical lessons we learnt from Well No.1. What was our success? What were our failures? What can we improve? What can our contractors improve on? Who was the weak link? What can we do about that so that we learn from the lessons of Mukuyu-1, so that we get a better Mukuyu-2?

For Zimbabwe, we are very excited because I can share with you that in other jurisdictions, like East Africa, they had to drill more than 200 wells before they could declare a commercial discovery. For us to hit hydrocarbons in our first well is a huge, huge, huge, huge plus, and we are very proud of that.

We have kept everyone abreast. In my 30 years in the industry, I have never seen a project which has had such a robust consultative process with our stakeholders – right from the Presidium, the ministers, provincial ministers, the minister of mines, the minister of energy, the local political leadership, the local traditional leadership, and the people on the ground. We have gone on the ground. We have employed locals. In the last campaign, we had 200 local people all trained from scratch.

In terms of our interface with the community, we have employed two locals as community liaison officers. They are the interface between the project and the local communities. Anything that we want to do in the community, our liaison officers lead the way. They hold meetings which are very well attended by everyone – from the councillors, the local leadership, men, women, and children. And all questions and fears are articulated.

These meetings are held at ward level to make sure that there is total, total, participation. We also liaise with our local chiefs. Even before we started the project, we went to see our local chiefs. The project is under the jurisdiction of 8 chiefs – 4 chiefs in Mbire and 4 chiefs in Muzarabani. We visited each and everyone of them.

All the chiefs agreed that, because we are in Zimbabwe and we are in Africa, we need to follow our traditional norms, so we had to do traditional ceremonies which were guided by the chiefs. This was coincident with the time of Covid-19, so while we had intended to have one big traditional ceremony, we had to separate them because of Covid. So each chief did a separate, smaller ceremony in order to manage the Covid protocols.

I am happy to say that all the 8 chiefs were involved in our traditional ceremonies. So we have earned our social licence, and we continue to earn our social licence with our local leadership – from the traditional and local perspective.

We have also recognised the fact that the community has got certain expectations, which came out of our stakeholder consultations and environmental impact assessment. The project is fully licensed from an environmental perspective, through the Environmental Management Authority.

But the community came to us with their wish list of expectations. And we took this list and re-arranged them into what we now term as immediate, medium, and long term. We haven’t waited until we go into commercial production to start meeting some of the community’s expectations. So we have got a fully-fledged corporate social responsibility programme that is directed by the aspirations of our communities.

We identified water, sanitation and health as the first things we needed to address. So we have drilled a number of boreholes in the communities. We don’t dictate where the boreholes go, the communities tell us where they want them. We’ve also upgraded some of the handpumps that already existed into solar boreholes. We’ve put up water tanks, and updated clinics and maternity wards. As we speak, we are upgrading a 42-km road from Muzarabani to Hoya where we are going to put our camp.

This is our commitment to the social responsibility we have for our communities, and the communities are grateful because they are part and parcel of what we do. We do not pay much attention to naysayers because we think we’ve got a job to do and we don’t want to get distracted.

Any Zimbabwean is free to go to Muzarabani and Mbire and see for themselves what we are doing within our communities and talk to our chiefs, councillors, and local leadership. I don’t think there is space to try and defend ourselves. The communities are there to defend us, because we are closely knit with them, and we talk to them every day. We are part and parcel of the Muzarabani-Mbire family.

We participate in national events like independence days, so we don’t feel like we don’t belong. We belong. And we’ve got a job to do. We need to build our country, Zimbabwe. We need to focus on delivering a second well. We have promised the Government of Zimbabwe that we are going to do a second well as a follow-up of the first well.

In this type of business, we make top decisions based on technical results, and if the technical results are saying stop, we will stop. We will not spend anymore cent. But in our case, our decisions are all green light, go, go, go. And we are progressing with the project.

Q: How far will the second rig be from the first one?

A: It will be in the region between 5 and 10 km from the first one.

Q: How big is your area of exploration?

A: We are exploring an area that was initially 100,000 hectares. But through our collaboration with the Zimbabwe Sovereign Wealth Fund (ZSWF), we now have access to licenses that were issued by the ZSWF, and as a result we have assumed the exploration rights granted by those licenses. So the search area has increased to 700,000 hectares.

If I can put it in a layman’s language, it is like finding Mr Huni who is somewhere in Harare. But is he in Borrowdale? Is he in Mabvuku? Is he in Mount Pleasant? Or is he in Epworth? So it is a basin-wide exploration. It was never meant to be a one-well operation.

But because – and rightfully so – our communities and our people are so expectant of the results of this project, people sometimes forget that we are still in exploration. They want to judge us as if we are now in production, but it is all still exploration.

And so you drill a multiple of wells, and these multiples of exploration wells will then allow you to compute the volumes, the flow rates, the porosity, and the permeability of the rocks. There are a lot of technical parameters that we manage. So that when you go into production, you will have information to say “ok, we know that there is oil and gas in Harare, we’ve done a well in Borrowdale, we’ve done a well in Mabvuku, we’ve done a well in Epworth. Now for us to produce, how do we join all these wells to go into production?”

So exploration is one phase. After that we go into what we call a development phase. That now leads us into production. So it was never ever going to be a one-well affair. And it’s never a one-well affair.

Q: Do you have a timeframe for the exploration stage to end and you go into the development stage?

A: Being Zimbabwe, we always want to be innovative about things, and for this project we are trying to be innovative, especially from the second well. We are trying to say should we repeat the success of Mukuyu-1 in Mukuyu-2, can’t we look at a scenario where we do an early-stage monetisation of whatever comes out of Mukuyu-2?

So these are our small modular plans – if we get gas in Mukuyu-2, we can do gas-to-electricity for example while further exploration continues. So we will have a mix of early-phase monetisation of any opportunity while we continue with the exploration.

When you look for oil and gas, there are a number of things that you look for. One, do you have the rocks that have capacity to generate oil and gas buried underneath? If yes, do you have the right structures or trap sands that could trap the oil and gas? Three, do you have the right mobility? Can your oil and gas move within the rocks? That is when we talk about porosity and permeability. And four, is the timing right?

Sometimes you get oil, sometimes you get gas, sometimes you get a mixture of oil and gas. In our case, we think we have got a mixture of oil and gas.

Q: So when exactly is commercial production going to start?

A: Like I said, we are trying to have a hybrid approach where the exploration continues, but we start on a modular manner. So if we are looking at the low level, early-stage monetisation, that could start within the year while the exploration of the basin continues.

We are very cognisant of the fact that the people of Zimbabwe are expectant, the country is expectant, and the economy is expectant. So whatever we find, in other countries I am sure you have seen on TV where they have got these oil wells and a big fire flaring the gas. That is to manage the accumulation of gas, so you burn it out. For Zimbabwe we don’t have that luxury.

So we are saying instead of flaring, let’s capture that gas and monetise it early. With technology these days you can have generators that come in containers. People are crying because of load-shedding, so if we can have these generators that can generate 50 MW, 100 MW, 250 MW or 300 MW of electricity, that will go a long way to help the country.

So we are cognisant of the fact that the country and everyone are expectant, but again we need to allow the technical processes to unveil while at the same time we are alive to take advantage of any early-stage monetisation or commercialisation opportunities for whatever we find.

Q: In Africa, we always come to the question of ownership. Other African producers of oil and gas are getting about 5% or so, in fact less than 10%, from their hydrocarbon resources. The rest is going to the foreign companies exploiting those resources. So tell us, what will be the ownership structure in the Muzarabani-Mbire project? How much is Zimbabwe as a nation going to get from all the work you and your colleagues are doing at Muzarabani?

A: Thanks for asking that pertinent question. With the current legislation, anyone who is extracting any mineral commodity in Zimbabwe, be it diamonds, gold, coal or gas, you pay a royalty to the Government of Zimbabwe. The highest royalty is in diamonds which is 10%. Coal is 2%, gas 3%, this is the current legislation.

When I talk about this project, I wear two hats. The first hat is that of the project promoter and shareholder. The second hat, which is no less important, is my Zimbabwean hat. So wearing my Zimbabwean hat, we have approached the Government of Zimbabwe and said, “please Sir, the world over, yes we will still pay the royalties like everyone else who is mining, but over and above that, the oil and gas sector works on a production-sharing agreement.”

What that means is that the Government of Zimbabwe will be eligible for a share of the production, and we are currently working on that production-sharing agreement document. We have been working on that document for the last 3 years with the Government of Zimbabwe – the Attorney General, Ministry of Mines, Ministry of Finance and all that. And that document is almost done.

In other jurisdictions, the production-sharing agreement entitles the host nation to take anything between 26% to 60%, but we think that at the end of the day, the Government of Zimbabwe will be eligible for close to 50% of whatever product comes out of this project, without – and this is very important – putting a single cent in the project.

Q: That’s good to hear.

A: Yes. And we have benchmarked it. We have shown the Government of Zimbabwe what other countries do, and we have said to them that the current legislation – in fact we could have kept quiet about it – only gives the government 2% royalty, plus taxes and all that.

But over and above that, we have proposed a production-sharing agreement with the Government of Zimbabwe, and rightly the government has said “thank you, we’ve seen it but we don’t want to sound like we understand this, we want some external counsel”, and that process has been done.

The government has received two reports from external counsel, and we are now in the process of exchanging notes. But there is a production-sharing agreement. What’s in it for Zimbabwe is a free share of anything that comes from Muzarabani and Mbire, and we think that it will be to the tune of 50%. And we carry all the risks.

The way to look at it is that the Government of Zimbabwe is saying “these resources belong to Zimbabwe. You guys – Geo Associates, Invictus, and OneGas – you just happen to be the contractors that we have awarded the licence to explore at your own risk, because you said to us that is what you do. So we will allow you to use your own money to explore. If you find anything, we will allow you to recoup your costs plus a small premium, and whatever is left on the table you share with the Government of Zimbabwe”.

And this is what the production-sharing agreement is saying. It is a thick document. It covers all the accounting procedures, and accountability and governance issues.

We think it is a better proposition than ownership. Why? Because if it is ownership, for example we are now going to do Mukuyu-2 and we will spend probably another US$18m or US$20m, so if it is ownership and you own 50% of the shares, you have to fork out your 50% of the costs.

But we are saying we will take responsibility of all the costs. Whatever comes out of production, 50% goes to the Government of Zimbabwe for free. And the government can elect to take that as products or we can co-market it and turn it into cash. They can elect to do whatever they want. That is why governments end up establishing their own refineries and whatever.

Q: Talking about refineries, are you thinking of doing one here?

A: Yes, we are thinking of doing it. We are firm believers of value addition. We want to take lessons from our African brothers who discovered oil and gas before us, where they have been successful and where they could have improved. So we have come to the party late, but it is also a good space to be in because we can learn from other people’s mistakes.

Q: Am I right to say that this good deal is coming to Zimbabwe because some sons of the land are right inside the administration of this project? In other African countries, the foreign companies exploiting the oil and gas resources give them very bad deals because there is no son of the soil inside the bubble to look after national interests. You said a moment ago: “We could have kept quiet and paid the Government of Zimbabwe the 2% royalty the current legislation says we should pay,\.” Now the presence of some sons of the soil in this project has changed all that. Is that how you see it?

A: That is why I said I wear two hats. I have my shareholder hat, but I also wear my patriotic Zimbabwean hat.

Q: What message do you have for the other African oil and gas producers, including the new ones coming to the party. What should they do to get good deals?

A: I think the message is very clear. I have worked in the corporate sector for more than 25 years and most of these entities were foreign – Canada, Australia, London – and we were doing the heavy lifting, finding deposits for these guys.

For Zimbabwe, the country took a deliberate decision to say we want to see local participation of our sons and daughters in the mainstream economy, and that is why I never left Zimbabwe to go and seek work abroad. I can work anywhere in the world but I believe in the geology of my country, and I also believe in the leadership of my country.

So the governments of Africa just need to lay the foundation for these sons and daughters that they have spent so much money on to send to school, to give back what they can. And this is what we are doing here. We are driving the process. Yes, we need expertise and funding, but the mentality should be home-driven.

CAPTIONS

Pic 1:

Paul Chimbodza, Managing Director of Geo Associates: “Do we have oil and gas or not? That was the reason we drilled Mukuyu-1. And we answered that pertinent question. And the answer was yes! We do have hydrocarbons in the Muzarabani Basin”

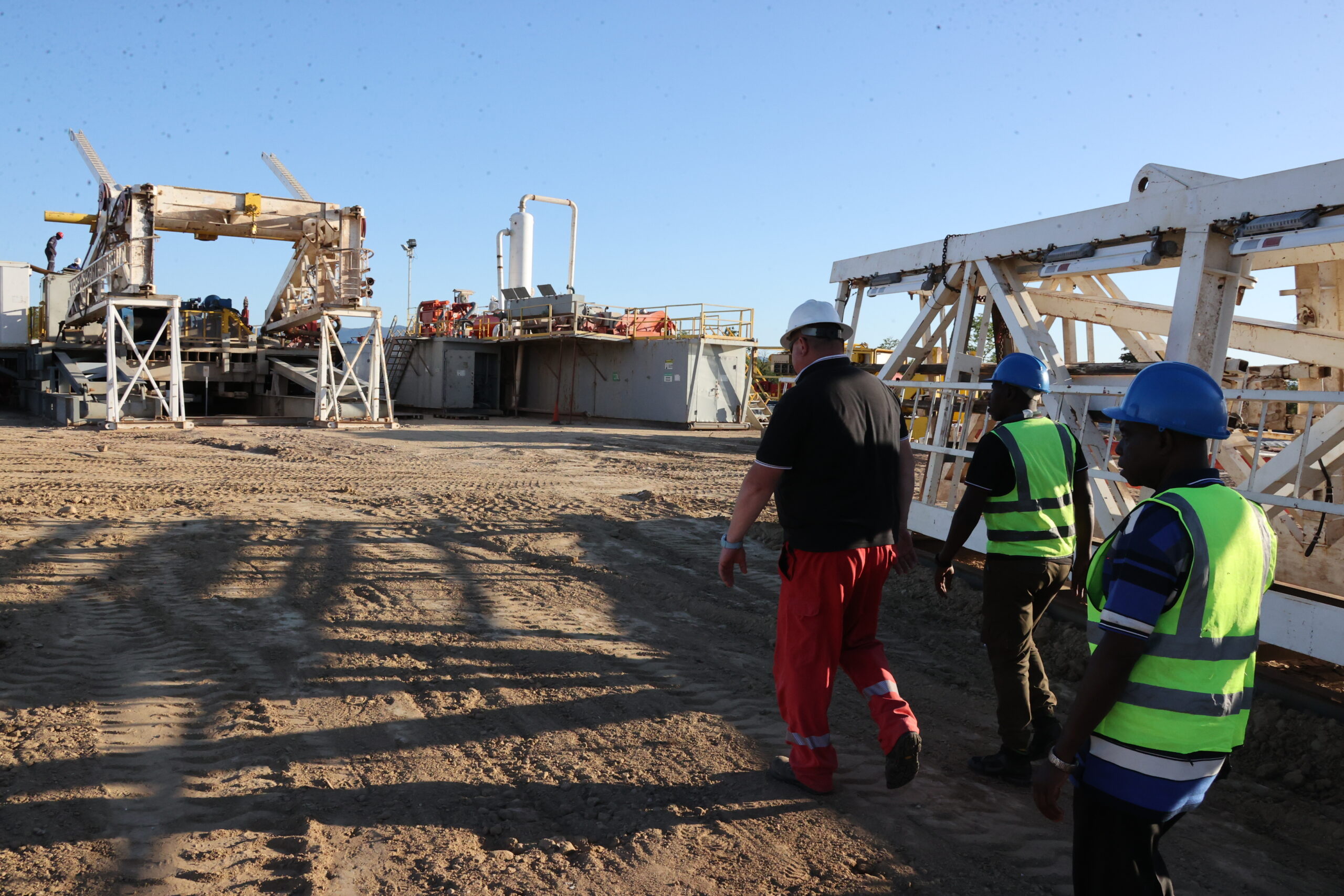

Pic 2:

A historic site: Part of the rig that drilled the Mukuyi-1 well that confirmed the presence of hydrocarbons in the Muzarabani Basin

Pic 3:

Paul Chimbodza: “In other jurisdictions, the production-sharing agreement entitles the host nation to take anything between 26% to 60%, but we think that at the end of the day, the Government of Zimbabwe will be eligible for close to 50% of whatever product comes out of this project, without – and this is very important – putting a single cent in the project”

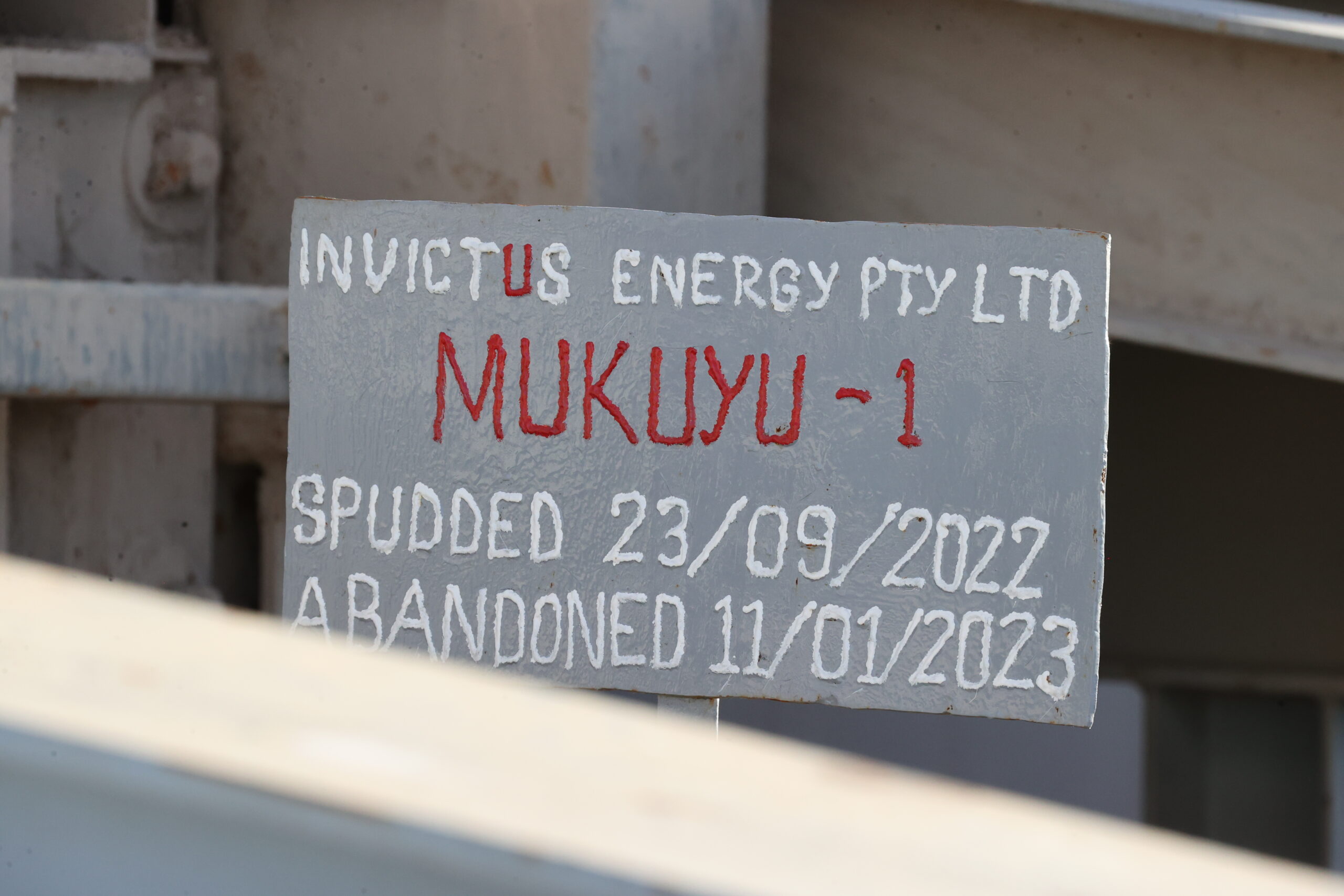

Pic 4:

The sign by the entrance of the road that leads to the Mukuyi-1 rig site

Pic 5:

Paul Chimbodza: “When I talk about this project, I wear two hats. The first hat is that of the project promoter and shareholder. The second hat, which is no less important, is my Zimbabwean hat”

Pic 6: A team of visiting Brick by Brick editors being conducted around the Mukuyi-1 rig site

Pic 7: Paul Chimbodza: “With the current legislation, anyone who is extracting any mineral commodity in Zimbabwe, be it diamonds, gold, coal or gas, you pay a royalty to the Government of Zimbabwe. The highest royalty is in diamonds which is 10%. Coal is 2%, gas 3%, this is the current legislation.”

Pic 8:

For the records: This board shows when work at Mikuyi-1 started and ended